Pre(r)amble

This is part of a(n aspirationally) series of posts documenting some of the process of (building|cat herding an AI agent to build) an easily hosted Python teaching tool built with just front-end JS and a WASM port of MicroPython.

- You can find Part 1 here

- This is Part 2!

- You can find Part 3 here

- You can find Part 4 here

- You can find Part 5 here

- You can find Part 6 here

What we had before

The outcome of the previous week’s achievements was pretty satisfying since I’d tried and failed to solve the problems of having a responsive WASM Python runtime for user code before. Being able to lean on the agent to do things like make changes to C code where I knew what the outcome needed to be, and knew how it needed to work, but didn’t know what to do to make it happen was so valuable.

By the end of it I had a Micropython runtime running client side and being able to write, execute, and interrupt user code. I still have a nagging feeling that there will be some edge cases to discover where everything will break horribly and we’ll be diving back into compiling C code again, but for now it’s just a feeling. I have a virtual filesystem that the Python code can access, and a basic snapshot system for version control. Finally, I had a configuration system where scenarios could be loaded into the browser with instructions, starter code, and live pattern-based feedback for code as well as IO.

What’s happened since

On my list of priorities for the next features to implement were:

- Unit tests for user code so program behaviour can be verified against the instructions

- A configuration authoring interface so I didn’t have to write JSON all the time

- Methods for loading configurations into the page

-

01_editor_instructions

01_editor_instructions

-

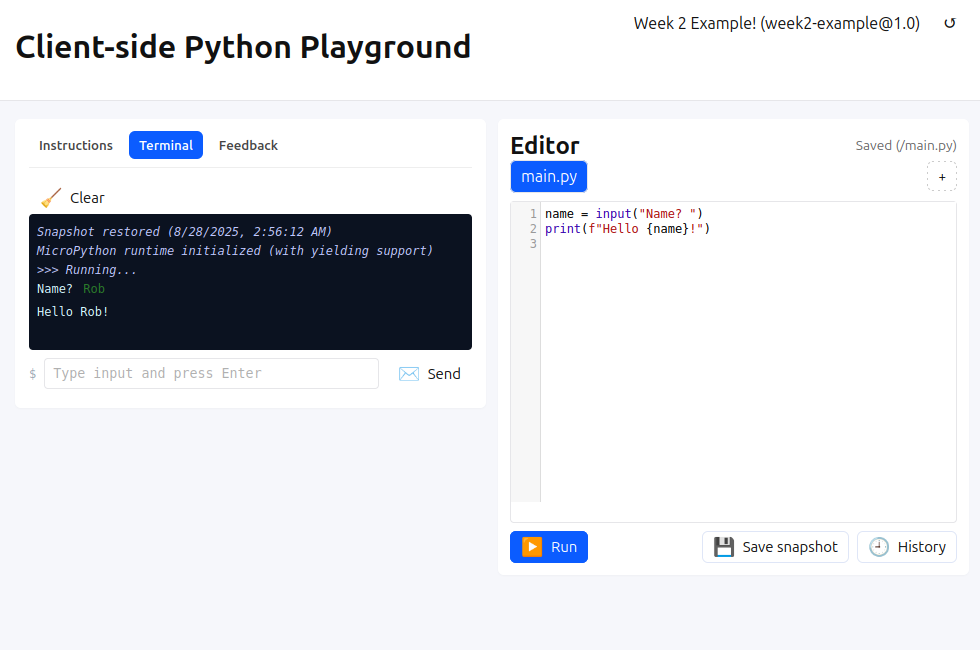

02_editor_terminal

02_editor_terminal

-

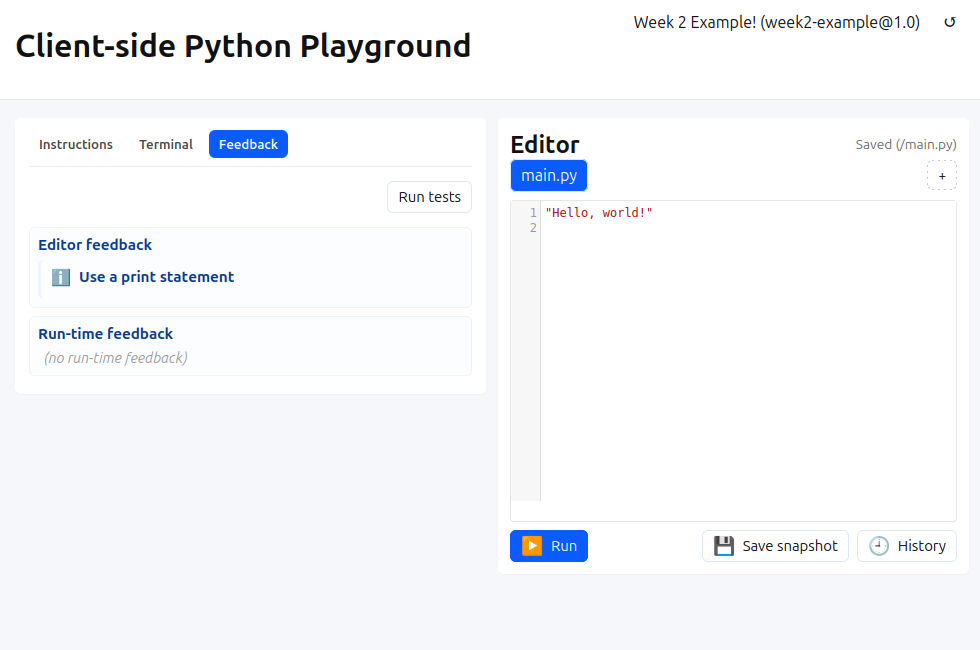

03_editor_feedback_no

03_editor_feedback_no

-

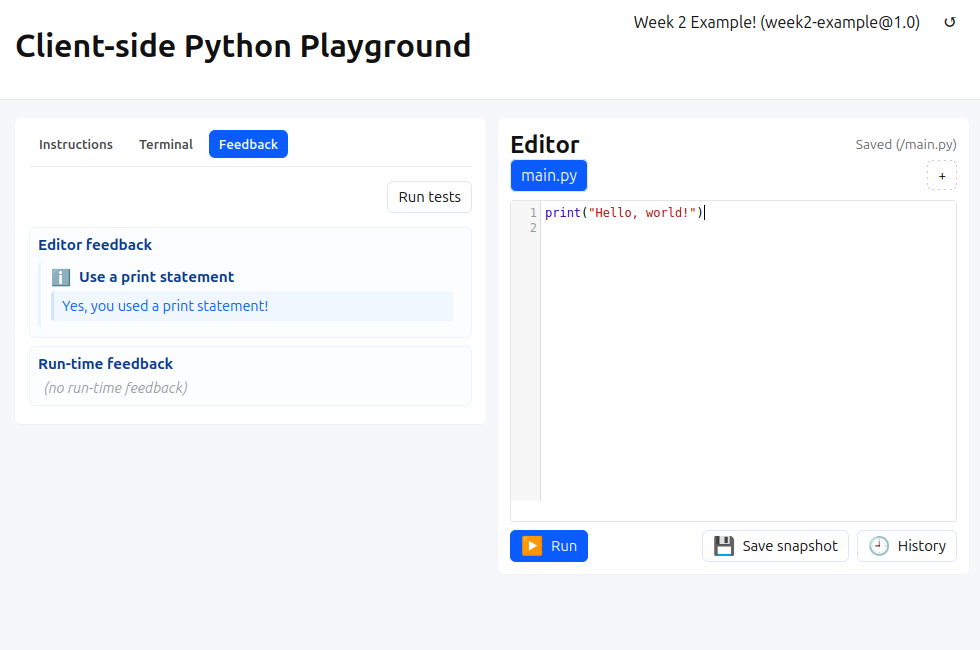

04_editor_feedback_yes

04_editor_feedback_yes

-

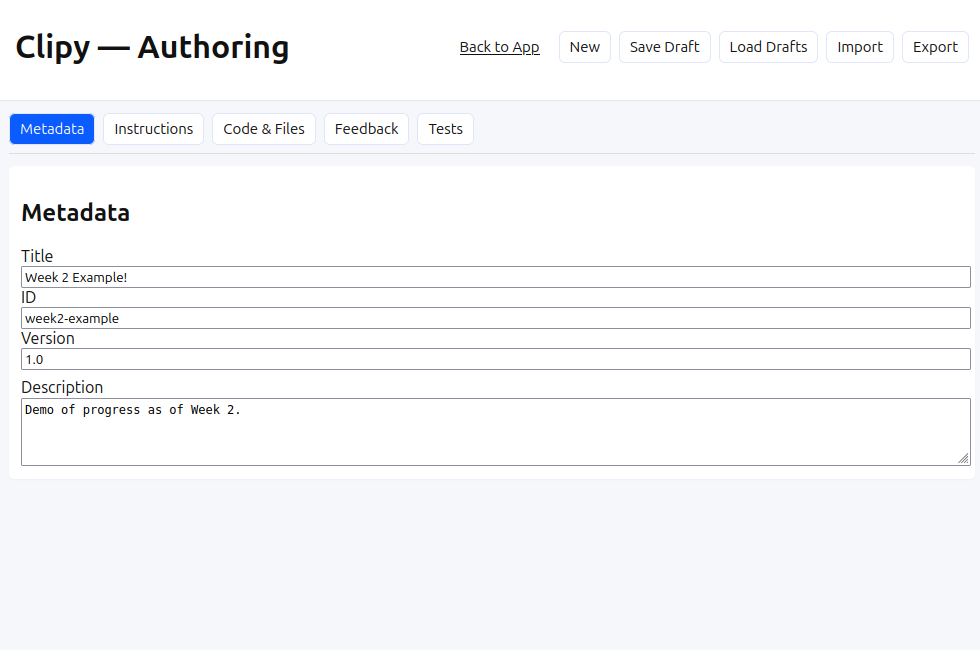

05_authoring_meta

05_authoring_meta

-

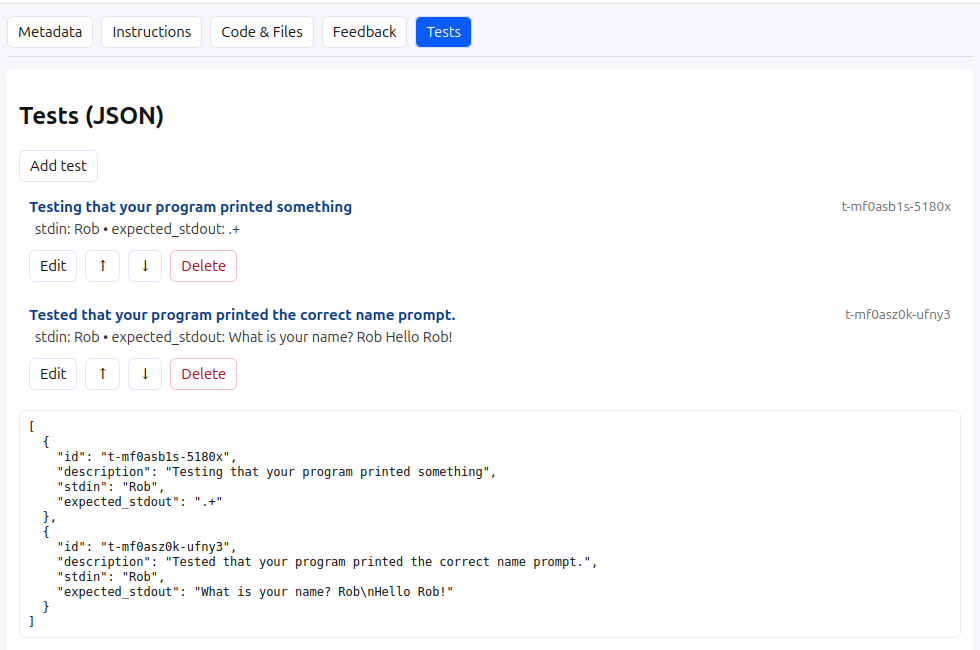

06_authoring_tests

06_authoring_tests

-

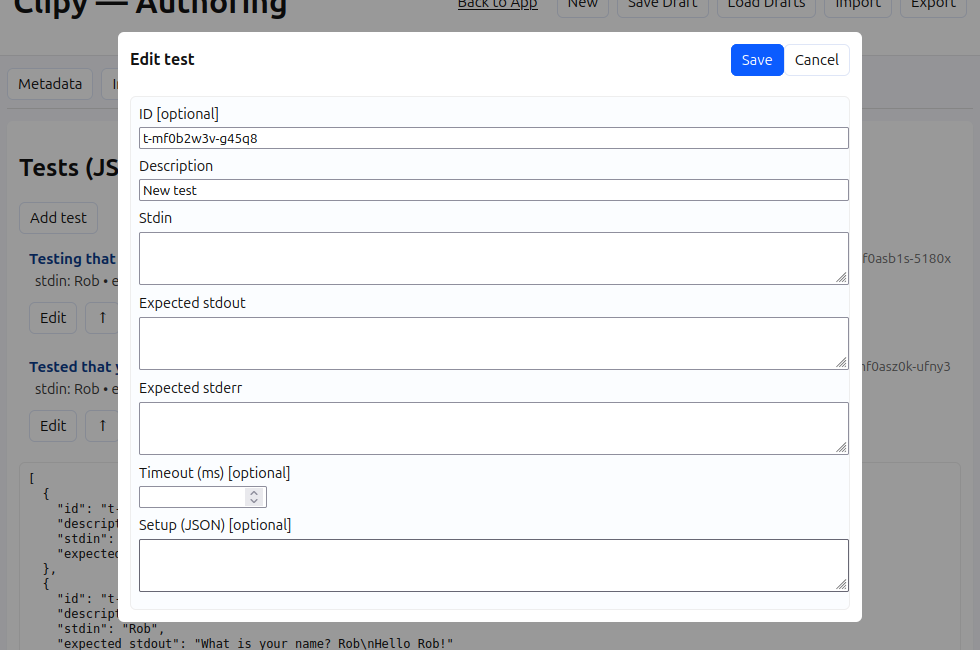

07_authoring_tests_single

07_authoring_tests_single

-

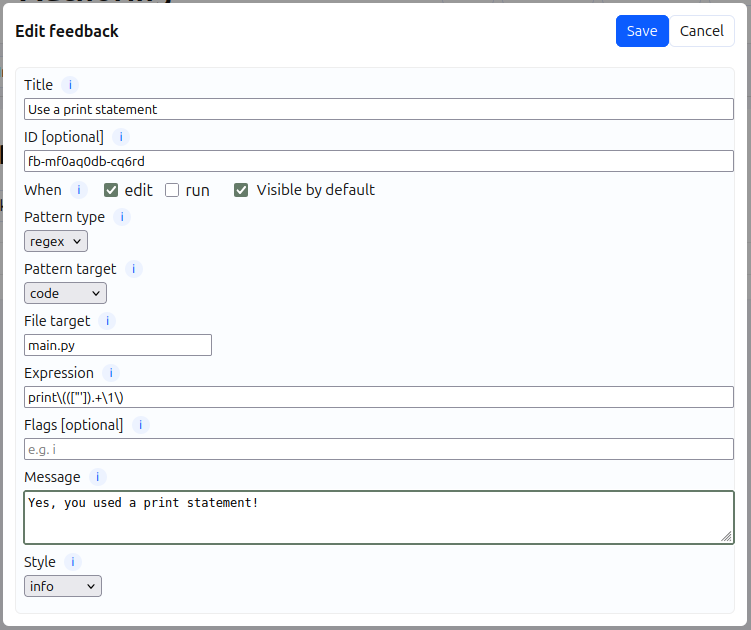

08_feedback_authoring

08_feedback_authoring

-

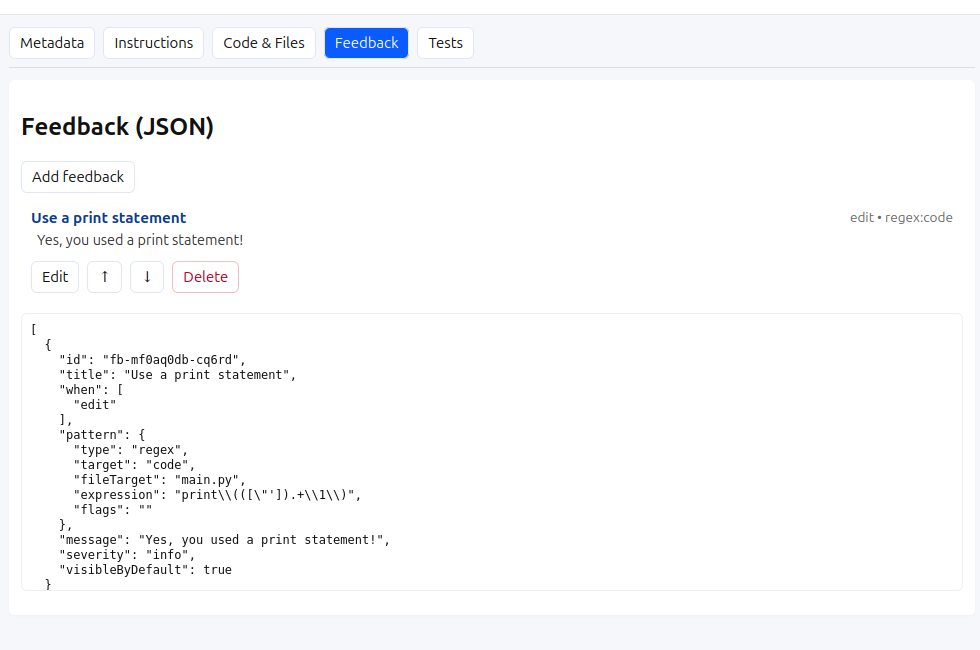

09_feedback_list

09_feedback_list

Is this going to be in the test?

Testing has been a bit of a ride. To start with I wanted to re-use the same Python runtime

as the user code to run the tests, but I ran into way too many issues with state, rewiring

stdin, stdout, and stderr so that it was only visible to tests, and just plain implementation

issues, so a couple of reverts later, I went with firing up another runtime in an iframe

and just doing the testing there, passing info back to the main page.

input not an input?

So I know I said something about rewiring things like stderr and stdout but actually

that turned out to be such a mess that actually what I did was just treat it all as stdout

and do some pattern matching for tracebacks. I’m not proud.

Who knows, this could be an opportunity later on to just compile something into the runtime to make it easier. After all, one of my main realisations from the previous lof of work was that it doesn’t matter what the original Python was meant to do, it only matters whether it looks like it’s doing it to the user, and if their code is implemented in a real runtime it does the same thing.

So far I’ve implemented testing for stdout, stdin, and stderr. This is all focused on

program behaviour, not implementation. Down the road I want to implement richer testing of

the program internals.

One of the interesting things about doing the tests for stdin was again a difference in

how the user-facing code works compared to the testing framework. User code is interactive -

one of the frustrating things about working with the agent was it kept suggesting just

pre-collecting user input, shattering the illusion of interactive code (and also ignoring

the problems caused by non-deterministic inputs, such as in a while loop). With tests, we

can quite happily just build an input queue and feed the program as required.

I need to do some more rigorous tests of behaviour with mismatched inputs and expected inputs since for now there’s a bunch of ignoring of inconvenient things going on.

These are no spaces for braces

JSON is supposed to be human readable, which it is (mostly). However it is so not human writeable. Since the configuration for problems is done in JSON I wanted to have an authoring tool to create the JSON files, prevent dumb errors, provide documentation, and so on.

This was handled by the agent pretty well after writing up a spec document and getting it to identify gaps in requirements.

The outcome was a separate page that allows for configuration metadata, writing instructions,

building feedback, and writing tests. The latest configuration is saved and loaded from

browser localStorage, which has a nice side benefit of providing that as a data source

when loading in the main page. It has a pretty pleasant flow of: edit config, switch to the

app page, load the latest config automatically, run tests or feedback, and repeat. When I’m

happy I can export to a JSON file. I haven’t implemented it yet, but the plan is also to keep

configs as a more easily accessed list in IndexedDB so that if you’re developing on the same

machine there’s a lower friction way of editing configs over time.

But teacher, what am I meant to do?

When developing I have a few sample configurations sitting in a sub folder of the app so I can test various features, but if this is going to be something for people who are not me to use, I wanted to provide some flexible methods of loading configuration information.

I landed on a few different methods:

- Manual loading based off files stored with the app (not user friendly but easy for testing).

- Loading an authoring config file from localStorage (see previous section). Only for authoring testing.

- Upload a file manually (open a JSON config). Not very student friendly.

- Load from a URL parameter, either providing a file name (load from the config store) or a full URL.

The last one is much more user friendly - a teacher could just provide a link in an email, LMS, etc

and the page would automatically load the config that was specified. The problem is one I’ve

run into a fair bit when developing this - what about server settings? To load the file from

another site, it needs to allow Cross-Origin Resource Sharing. From what I gather, this would

require someone to host and access their resource files through something like GitHub using

the raw.githubuserconent.com method.

None of these methods are amazing, but again given the constraints of “hosted on a vanilla HTTP server with no special configuration” I think it’s about the best I can do, so all of them are implemented.

Introspection

This stage of the process has highlighted some interesting aspects of the agent workflow:

- I feel like I’m playing this weird hybrid role of product manager and tester.

- Ran out of the credits provided as part of my Copilot subscription part-way through the week, which cut off Claude, so I’ve mostly been working with GPT-5-mini. The difference in “AI-ality” (not “person"ality,surely!) is striking.

- There’s been a real difference in speed of development vs perceived speed of development this week, since a lot of it has been UI code, but a lot of it has also been fixing regressions (so many regressions).

- Testing (lots of plain JS and Playwright) has been interesting. One thing I’ve really not been enjoying is the feeling that instead of just running the tests myself, I should be asking the agent to run the tests because then it pays attention to the test output. This is super frustrating, and I’ve found that as I go on I’ve been trying to be more involved in the code myself because the alternave is so incredibly wasteful in terms of time and resources.

As I was taking screenshots for this post I realised that something was broken in stdin tests again.

So. Many. Regressions. 🤣🐎