Pre(r)amble

This is part of a(n aspirationally) series of posts documenting some of the process of (building|cat herding an AI agent to build) an easily hosted Python teaching tool built with just front-end JS and a WASM port of MicroPython.

- You can find Part 1 here

- You can find Part 2 here

- You can find Part 3 here

- This is Part 4!

- You can find Part 5 here

- You can find Part 6 here

What we had before

See last week’s post for some of the details and screenshots.

- AST feedback and tests with an authoring tool for building some customisable rules

- Test groups and run conditions for groups and individual tests

- Activity indicator on the feedback tab

What’s happened since

Here are some screenshots of the latest version with some of the new features.

-

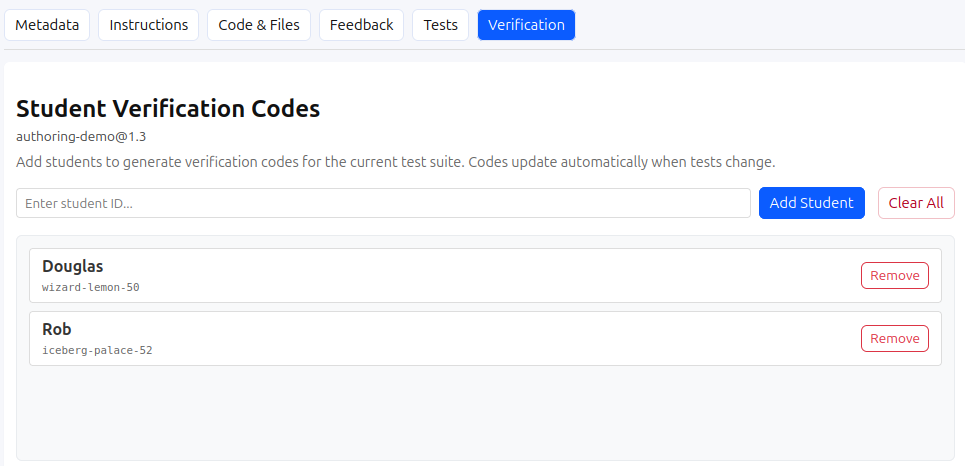

01_verification_authoring

01_verification_authoring

-

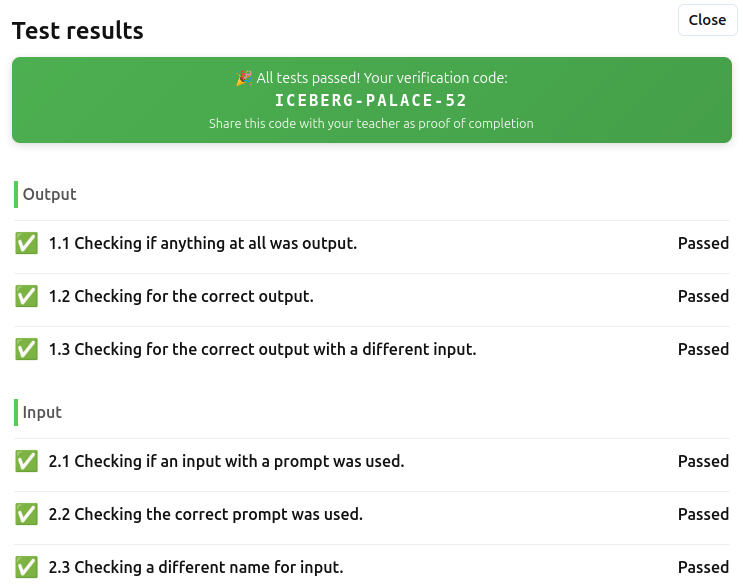

02_verification_user

02_verification_user

-

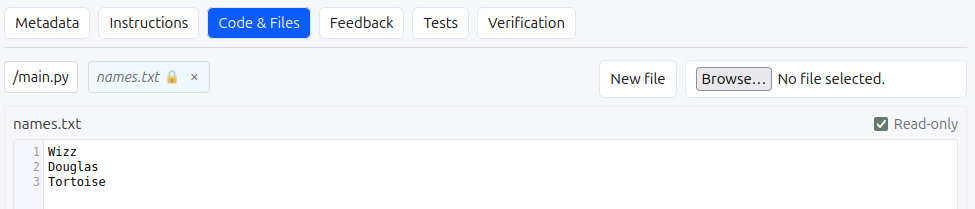

03_read_only_author

03_read_only_author

-

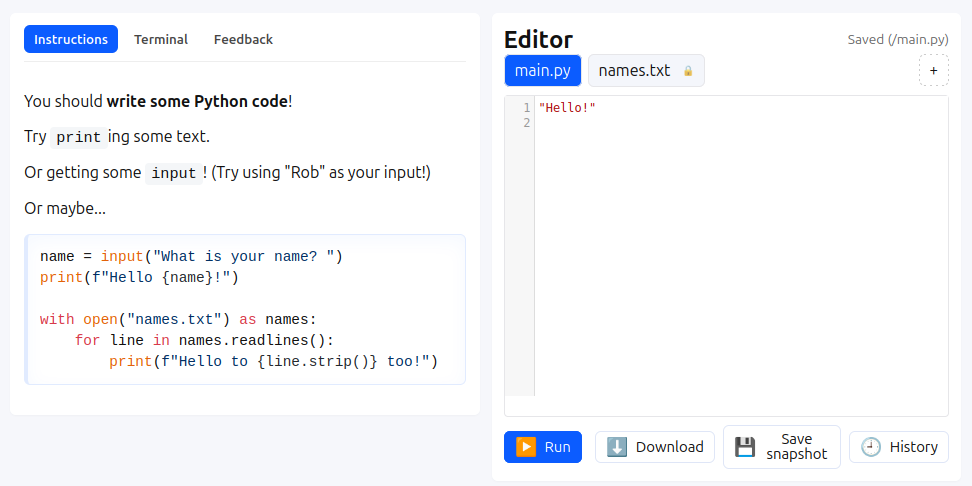

04_read_only_user

04_read_only_user

-

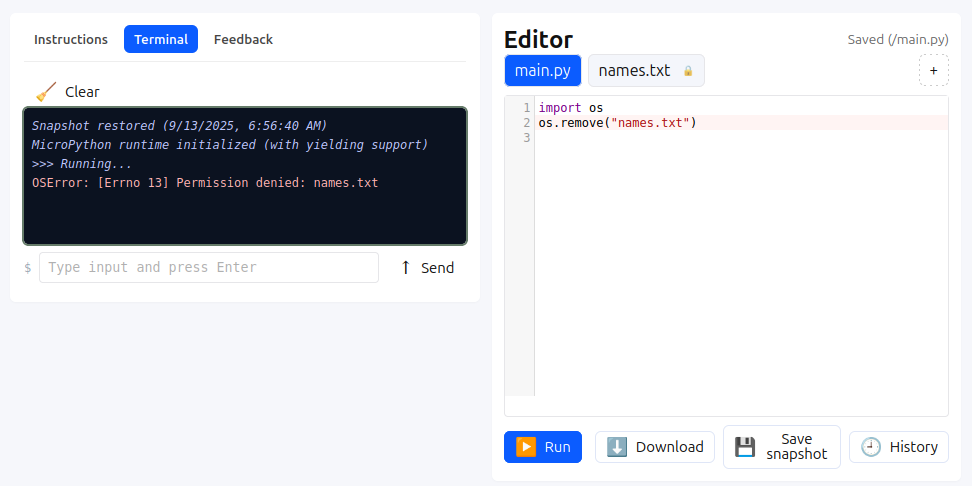

05_remove_protected_file

05_remove_protected_file

-

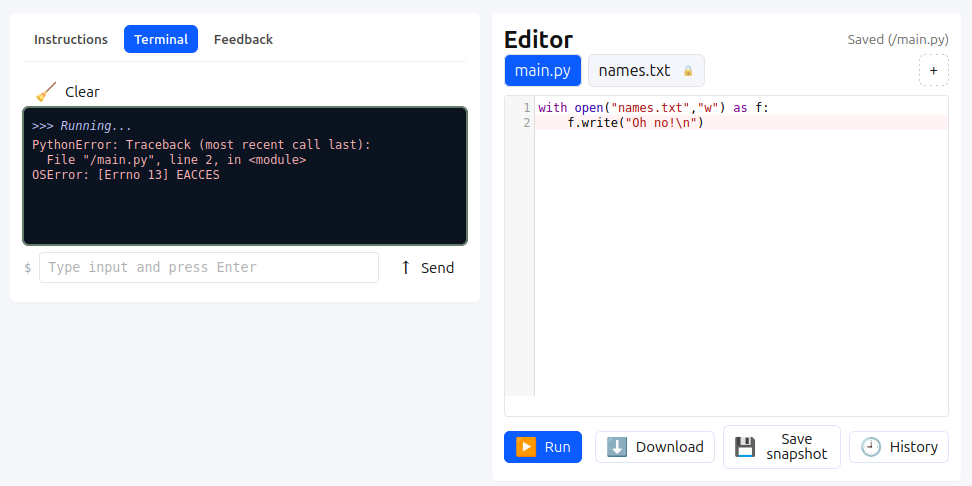

06_write_to_read_only

06_write_to_read_only

-

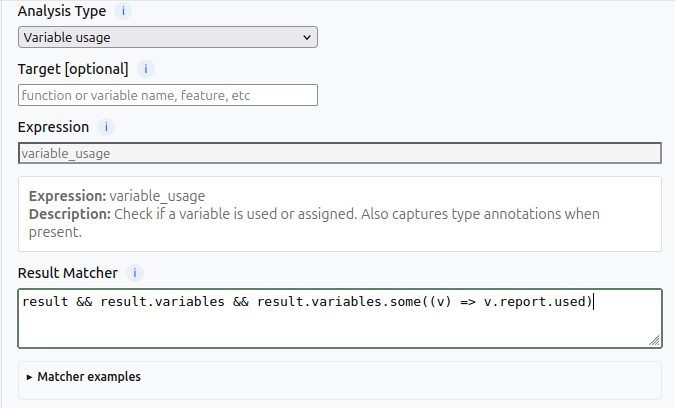

07_ast_rule_interface

07_ast_rule_interface

-

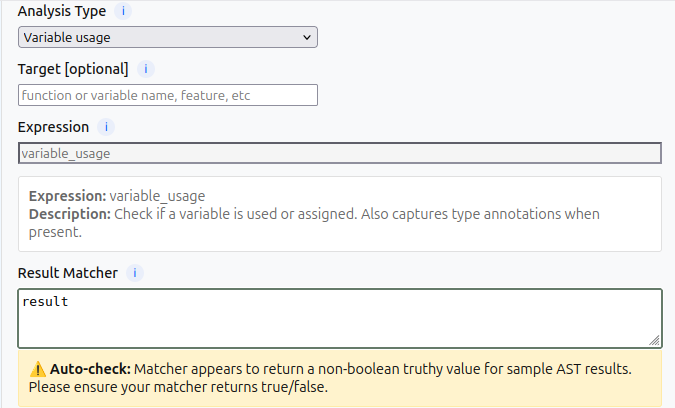

08_ast_truthy_warning

08_ast_truthy_warning

-

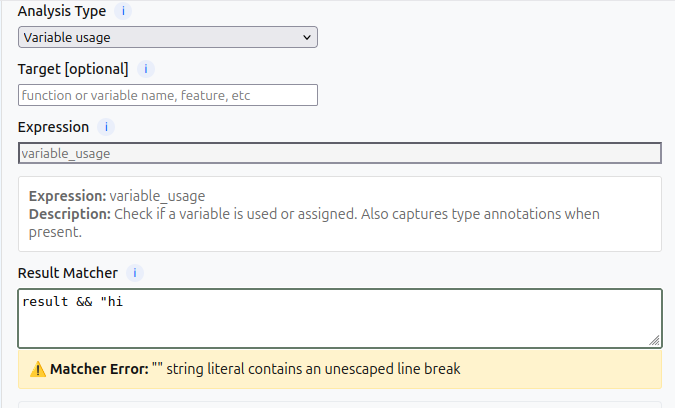

09_ast_syntax_warning

09_ast_syntax_warning

Student verification codes

Although this is designed to be a tool predominately used by students, I’m a teacher, and having some feedback from students about whether they have successfully completed a problem scenario is a nice to have. But how do we do this in an environment specifically designed to not require any server infrastructure?

The answer is obviously hashing! So I added an optional student identifier to the UI, and when all the tests have been passed, if there is an identifier present, the student gets presented with a human-speakable code (two words and a number) that is built from a hash of the test suite, the day they ran the tests, and their student identifier.

In the authoring interface, the teacher can enter any number of student identifiers, and will be shown the current verification codes for the problem config that has been loaded. This obviously doesn’t give the teacher any idea of how the student has solved the problem, but it’s a lightweight first step in a conversation.

Authoring improvements

There were a few improvements to the authoring page this week, mostly focused on making tests and feedback easier to author and more flexible.

- AST rules now have some light syntax checking of the rules, so will present an error and prevent saving if the expression is invalid or only truthy rather than a true boolean

- Additional files can be added to tests that override the user workspace, so allow for checks against hard-coded results of file use problems

- An option for partial or full string matches in feedback and tests was added to make it easier to write more flexible or strict feedback and test rules

Read-only file support

I added support for read-only (protected) files into the user workspace and wow did the agent ever have a hard time with this one. Files can be marked as read-only in authoring which both prevents the user from writing to them and also prevents deletion through the UI as well as with user code.

This is where I really started to run into some of the issues with using a client-side approach using Micropython. The two bundled ideas in this feature were file permissions and file ownership, both wrapped in a virtual filesystem bundle, trying to isolate authorship and userland code all on the user’s device.

This feature came with another exciting rabbit hole. When I was testing whether files had

actually been deleted (reconciling the tabbed file UI with the virtual filesystem that

Micropython accesses) I ran into an issue where an os.listdir() was taking 7 seconds

to run. It turns out the agent had added a boatload of system tracing into the code and

so something simple like “what are the files please?” turned into an insane mess of checks

and conditional console output.

Micropython’s edges

As I write more testing code, and put the (hopefully final) set of features into user workspaces and the authoring interface, it’s starting to become apparent where the hard edges are in using Micropython instead of something like Pyodide.

Error handling is something that Micropython does a bit differently. It doesn’t come with the lovely expansive tracebacks of regular Python (that’s been improved so much in the last couple of major versions), and so there’s a bit of a divergence between what the student would see running their code in this app vs in a desktop version when things go wrong.

Part of me wonders how much this is an actual problem however. As a teacher who has used Python for over 15 years now, particularly in days of yore when the popular programming languages in schools tended to be things like Visual Basic, I often think about whether it matters if we’re “teaching Python” or “teaching programming”, particularly as features like the walrus operator come out that have the potential to change the way we think about how control flow is written in the language.

The other edge I’m starting to run into as I build out a library of test configurations is modules and the standard library. A really common library to use with students is CSV. There are lots of examples of CSV data out there, and it’s convenient to export from spreadsheets and then use with code. However, CSV isn’t part of the Micropython stdlib.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if CSV wasn’t such a hot mess in terms of edge cases and we could do simple parsing, but sadly that isn’t the case.

I’m squinting at Pyodide and starting to wonder how much more involved it will be building the same sort of support for the async JS-based workflow I’ve got going here with Micropython, or whether there’s a better solution with full-fat Python. (Ideally a better solution that doesn’t involve completely rewriting the whole app!)

(A)Introspection

Back when I started this project everything was being written into one big main.js

file. Even after the first couple of working features appeared, this grew into something

like 3000 lines of JS, and this was the point where it became really obvious that

unless it got split out into feature-based files it would be completely unmaintainable

(particularly for the agent, which has really struggled with larger files).

Since then, I’ve been watching each of the modules getting bigger and bigger. Doing the refactor of the main file was horrible, and had a couple of false starts while I figured out a way of getting the agent to tackle the problem in a good way that didn’t get it stuck.

I’m peeking around my fingers at a time in the not-too-distant future when I’m going to start paying attention to just what is in those modules, since I got a bit of a look when trying to get to the bottom of the issues with the read-only file feature this week, and the amount of duplicate code, debugging code that’s been gated behind flags, etc. Slimming things down once things are “complete” is going to be a ride.